I tend to see Alexander as a man made by his culture. Macedonian kings were expected to win wars and provide loot. Furthermore, his society named men heroes for prowess in battle and personal bravery, not selfless public service. It was deeply agonistic, with zero-sum competition and a constant need to prove one’s personal excellence (aretē). Such demonstrations brought kleos–fame–and elevated one’s personal timē–honor or public standing. Humility was NOT a virtue, and there were no poor men, only rich men in the making. ;)

Put all that together, inject it with a hefty dose of testosterone, and you begin to understand Alexander (and larger Macedonian society).

Modern attempts to paint Alexander (ATG) as a hero or a villain often depend on modern views of virtue, not ancient ones. We want our heroes to be Captain America, or Frodo Baggins. Good-hearted, honest, humble, sometimes reluctant heroes. They’re driven by a sense of SERVICE, not a desire for KLEOS.

THAT IS EMPHATICALLY AT ODDS WITH ALEXANDER’S PRECHRISTIAN WORLD.Which makes him a hard sell.

I don’t plan to paint ATG as either hero or villain, in the usual sense. The very last line of Dancing with the Lion: Rise is highly ironic. I won’t repeat it here for those who may not yet have read the second book, but while Alexander absolutely means what he thinks in that moment, it’s a young man’s fancy.

It ain’t gonna be so easy.

Riptide has said they likely won’t publish further in the series, even before the first two came out, because the whole thing is a tragedy, not a romance. The first two books (or really one novel) have a “happily for now” ending, so they were okay with that. But we all know how the story ends.

It’s not a tragedy, however, because Alexander is a megalomaniacal villain. The protagonists of tragedies are called the “tragic hero,” after all.

I want to continue writing him much as I tried to in Becoming and Rise: a human being with flaws and virtues. And as with any tragic hero, the greatest flaws are often overdrawn virtues. Virtue turned inside out.

So again, if you’ve read book two, go back to the novel’s last line. There’s his tragic flaw in all it’s glory. His desire to uphold that, often in the face of serious reality checks, will finally break him in Baktria, where in the name of virtue, honor, and piety, he’ll commit a terrible atrocity that will drive Hephaistion from him for some time. Hephaistion is still loyal to him as king, mind, but he can’t stomach what happens on a personal level. It’s no silly love triangle, situational misunderstanding, or manufactured angst for “drama.” It’s a deep, fundamental ideological clash–the sort of thing that Real Couples face sometimes, and must then choose to accept and move beyond, or acknowledge is irreparable and separate.

Obviously, they’ll get over it. But it’s not immediate. Nor easily. And it will involve a lot emotional blood on the floor, from both of them.

Baktria is the pivot point in the series, where it moves from triumph to tragedy. Things that came together are now falling apart.

Less poetically, Alexander is discovering–post Gaugamela–that “compromise” is the ugly truth of successful politics. I love the line from Hamilton, George Washington to another brilliant, impetuous young man named Alexander: “Dying is easy, living is harder.” Alexandros may want to be Achilles, but Achilles DIED.

In Alexander’s case, “Conquest is easy, ruling is harder.”

Historically, at the end of his life, Alexander is much less idealistic: shrewder, harder, less trusting, and more pragmatic. Just look at his appointments at the beginning and in his last two years. Early on, he’s inclined to put the former ruler back in charge, as long as that ruler surrendered to him, and add a garrison. After returning from India, he discovers how many of those men (and some garrison commanders too) betrayed his trust. So he kills the lot and reappoints…virtually all Macedonians (and a few Greeks).

This is the opposite of Tarn’s “Brotherhood of Mankind” (which was enshrined in Renault’s The Persian Boy, and picked up as well by Stone’s 2004 flick).

This is Macedonian Realpolitik.

It’s also Alexander Disillusioned.

But he’s still not the devil. That’s too simplistic, and too modern. While I greatly admire Brian Bosworth’s scholarship (he was THE Arrian specialist), I disagree with his assessment of Alexander’s career in his 1986 JHS article, “Alexander the Great and the Decline of Macedon,” wherein he ends with, “That was the unity of Alexander–the whole of mankind, Greeks and Macedonians, Medes and Persians, Bactrians and Indians, linked together in a never ending dance of death” (12).

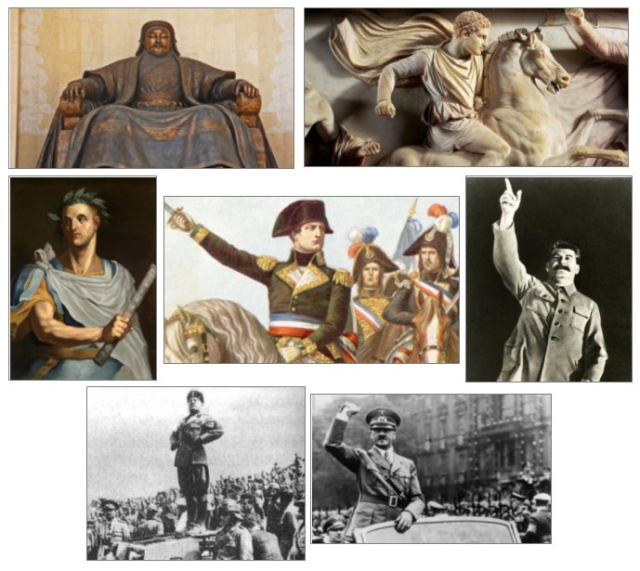

What Bosworth ignores is that nobody at the time would have seen conquest in itself as evil, merely how one went about it. And how Alexander went about it is, actually, a mixed bag. Maybe that’s his problem. He’s not ruthless enough to be admired for his sheer bloody-mindedness (aka, Genghis Kahn), but he did some terrible things, which kinda undercuts the “squeaky good guy” image he wanted to project–and I think genuinely wanted to believe himself to be.

We live in a post-WWI and post-WWII world, where starting a war to take land is sorta frowned upon. Even if Putin, Xi, and Erdoğan Didn’t Get That Memo. But that colors how we read Alexander’s career. We can’t and shouldn’t ignore Alexander’s atrocities, but casting him as a Hitler-esque madman says more about us than him. Alexander was NOT Hitler.

Walking that line is what I hope to do, going forward with Dancing with the Lion. There are ways to faithfully show ancient attitudes even while telegraphing to the reader that’s not okay. (Hephaistion often gets used for that, incidentally, both in what’s been published and in what’s coming.)

Back to Alexander…I suspect he was often frustrated with Macedonian pushback, given his need for approval/affection. (That’s one of the key elements of ATG’s character that I think Mary Renault hit dead on the head in her novels.) I also believe he was deeply disappointed in his Macedonian soldiers at times. As noted above, Tarn’s whole “Brotherhood” notion cracks apart when we look at what Alexander actually DID, not what he said in his “Reconciliation Banquet” speech. (Remember, ancient speeches are NOT what anybody actually said, but [maybe] the gist couched as a rhetorical exercise by the authors of these texts … regardless of whether it’s Thucydides’s “Funeral Oration” of Perikles, Arrian’s speech by Alexander after the Opis Mutiny, or Calgacus’s address to his troops found in Tacitus.)

Remember what I said about expectations for Macedonian kings? Win wars and provide loot. Alexander did that with bells on. As I’ve said before, here and elsewhere, he was the Energizer Bunny of Macedonian kings, just kept going and going and going….

Yet somewhere along the way, he decided he wanted to rule what he’d won, not simply plunder it. Opinions about Alexander’s “Persianizing” have waxed and waned. First, it was so tied into the “Brotherhood” concept that after Badian, et al., torpedoed Tarn, ATG was recast as simply a glorified marauder. Yet more recently, the pendulum has begun to swing back, pointing out that, rather than some ideological notion, perhaps it was pragmatic?

Yet many of his soldiers were not. They belonged to the former type. Plus, they’d been conditioned to think of themselves as conquerors, masters, etc. They’d proven their superiority on the battlefield. It’s the most simple sort of ethnocentrism: the “schoolyard bully” type. We beat you, so we’re better than you. They didn’t hold with Alexander’s myth-infused notions of conquest. To be honest, I don’t think Alexander held with them after Baktria. But I do think he understood that if he wanted to become Shah-han-shah of Persia, he couldn’t squash the Persians (and everyone else) under his heel.

IMO, too many modern historians are inclined to elevate the objections of Alexander’s soldiers, as if they are somehow pure of motive while Alexander isn’t, and he’s betraying them. That’s buying into ancient narrative bias. Let’s recast the whole thing in the modern era.

Reframed so, I think it easier to get beyond ancient pro-Hellenic source bias.

This is definitely something I’ll be playing with in the novel. It will NOT be “the poor, benighted troops are being mistreated by Ruthless Alexander.” But it also won’t be, “Alexander can do no wrong, and his men have no legitimate beefs.”

Life is NEVER that clear-cut.

NUANCE is all. And in the end, Alexander’s own virtues: his creativity, his ability to think outside the box, his insatiable desire to succeed, and his need to at least appear to be honorable…all these things will be his undoing.

(PSA: I reserve an author’s right to change my mind as I go forward and see how the series unfolds, but at least at present, this reflects my intentions, and some details aside, I think the gist will stay true.)