James Dobson, founder of the ultra-conservative Focus on the Family organization, reputedly said of the 2012 Sandy Hook mass shooting, “I think we have turned our back on the Scripture and on God Almighty and I think He has allowed judgment to fall upon us.”

As heartless as that sentiment sounds today when addressing the murder of 20 first-graders (and 6 adults) at an elementary school, it reflects a once-common theology that emerged about four thousand years ago in the ancient near east (ANE*), then bled into the Mediterranean basin and developed an astonishingly long half-life. It’s why some Christians (et al.) are so, so concerned with what their neighbors are doing behind closed doors. Or on their front lawns with all those Pride flags.

In some ways, ANE and Mediterranean religion had a lot in common, being traditional and focused largely on sacrifice/action (orthopraxic). Over time, some orthodoxic religions also arose in that area. So, first, let’s do some quick defining.

Orthopraxic religions focus on what one DOES, not what one believes. Performing the sacrifice correctly, honoring the gods/ancestors appropriately…that’s how one shows piety. Infringing against purity laws or other affronts to the gods (impious actions) can result in expulsion from the community. Fights over correct practice can lead to schism in a community.

Orthodoxic religions focus on what one BELIEVES. Thus, they need some form of authoritative text to determine what IS right belief, resulting in the emergence of a canon (e.g., Zoroastrian Avesta, Jewish Tanakh, Christian New Testament, or Muslim Qur’an). In Orthodoxic religions, wrong beliefs (heresy) can result in expulsion from the community. Fights over correct belief can lead to schism in a community.

(There’s yet a third focus, orthopathic, but that largely doesn’t apply here. “Orthopraxic” can also apply to ethics-based religions, but in this article, it applies to ritual/cultic behavior.)

Most religions have elements of all three, but it matters where the weight falls. Yes, religions can emphasize two sides of the triangle more heavily, less on the third, but even then, one point will be the chief measurement of devoutness among followers. This also help us understand why two religions might not understand each other very well sometimes. They’re trying to impose one set of “What religion is for” ideas on another, with entirely different assumptions.

The religions of the ANE and Mediterranean had much in common in terms of the purpose of religion: to maintain the health of a community. This depended on the piety of that communities’ members. Their gods weren’t moral in the modern sense, but could be jealous, fickly, and petty.

Why were they gods then?

Because they were immortal and more powerful.

Yet an important difference between (many) ANE and Mediterranean religions were the concepts of sin and “mesharum” (divine justice/equilibrium). If the latter existed (sorta) in Mediterranean society, “sin” really didn’t. Impiety differs as it can include ritual matters too. So, if murder (especially kin murder) created uncleanness anywhere and is a moral/civil matter, menstruation and sex also created uncleanness, but were not moral/civil matters defined as “bad.” So “unclean” ≠ “sin.”

To be unclean is a matter of cultic purity, different from moral purity. Yes, ANE religions also had ritual uncleanness, to be sure. And yes, some things that make one unclean also have intimations of “badness” without being so extreme as murdering someone. Yet I want to underscore the difference because it’s very real and too often ignored/misunderstood/unfairly conflated.

Many Mediterranean religions did not have “sin,” just unclean and impious. MORAL/ETHICAL matters were dictated by civil law and later, philosophic discussion. Not religion. Yet in the ANE, moral infractions were affronts to mesharum (divine order) and were therefore a religious matter. This oversimplifies, but smash-and-grab works for now. We find actions (like iconoclasm) in the ANE that didn’t often apply in the Mediterranean. (Iconoclasm is the deliberate theft, or in extreme cases, destruction of religious icons or structures.)

Yet what both groups shared was a sense that the gods had, well, “bad aim.” If people in a community were impious and/or sinful, that might draw the ire of the gods. Plagues were often seen as divine retribution for the impiety and/or sin of one or more members of that community, but not necessarily all of them. This led to the exile of impious individuals, as well as the ANE “scapegoat” ritual, et al. (If you’re familiar with the plot of the Iliad, Apollo punished the entire Greek army for the impious actions of Agamemnon.)

I could DIE from your impiety/sin committed in my town/community.

That makes your morality my business.

In addition, especially in the ANE, war on earth was believed to reflect war in heaven. Gods had cities and peoples, not the other way around. They chose you, you didn’t god-shop—hence Israel as a “chosen people.” Well, yeah, pretty much every ethnic group was chosen by some god(s). But as a result, if your side lost in a war, then—theoretically—your gods were weaker. Maybe you should go over and start worshiping their gods. Yet that didn’t sit well with most groups, so by the Middle/Late Bronze Age, we see an emerging idea that my god isn’t “weaker” than yours, rather my general “set forth without the gods’ consent,” or my god permitted the other god(s) to win for whatever reason…usually due to sin or a lack of piety among his (or her) people. Of course we find this in the prophetic literature of the Hebrew Bible, but it’s in a lot of other ANE literature too. Nabû or Marduk didn’t lose, they “went to live with” Ashur for however many years—although the winning side will portray the victory as Nabû and Marduk traveling to Nineveh to bow before (e.g., submit to) Assur.

Again, this is simplified, but we don’t see this sort of language used in Greece. Hera would not bow to Athena because the city-state of Athens defeated Argos, even if, as promachos (foremost in battle), Athena might be expected to win in any conflict between the two (as in Euripides’ Children of Herakles). Hera is still queen of the gods, and—even more—these are shared deities. We also don’t see it because notions of “sin” don’t apply and only a handful of wars were ever called “sacred”—all of them concerning Delphi and cultic purity. At least one of those is mythical, the second probably didn’t happen, and the third (which certainly did happen) was labeled “sacred” only by one side. Greek gods just weren’t seen to uphold justice the same way. Roman gods were more concerned with such things, but still not as we find in the ANE.

Ergo, the ANE faced the problem of theodicy: if god/the gods are good/just, why does tragedy happen?

Early explanations for tragedy were simple: those who suffer must have earned their suffering, sometimes referred to as Deuteronomic Theology: “good things happen to good people”/“bad things happen to bad people” (and maybe their neighbors too, by chance).

Pushback against this notion emerged around the same time a more nuanced view of loss in war emerged. People began to ask the corollary: “Why do bad things happen to good people?”

The (c. 1700 BCE) Mesopotamian Ludlul bēl nēmeqi (The Poem of the Righteous Sufferer) attempted an answer. About a thousand years later (600s-500s BCE), the Jewish Book of Job took it on as well. In both, the protagonist asks, “Why does Marduk/Yahweh punish me when I’ve been a faithful servant?” Both protagonists were previously wealthy/powerful, which was seen as divine approval. Losing that wealth/health suggested they had offended their god (and are being punished). Yet each one claims he did not sin—so why?

The answer in both works is similar: there’s not really an answer. Marduk restores Šubši-mašrâ-Šakkan, who ends the poem with a prayer of thanksgiving. Job has a chat with Yahweh, who essentially tells him, “You’re a measly mortal, don’t question me.”

The KEY element in both, however, isn’t the answer, but the assertion that a good person can suffer. They didn’t earn it; it just happened. They remained good and, eventually, their god restored them to their prior station, and then some.

Ergo, if you’re suffering, just be patient. Don’t curse God and die. (As Job is advised to do.)

Today, we may find such an answer wanting but need to recognize it for an advancement on the theology of tragedy.

Some, however, get stuck in these time-locked answers because they can’t allow their religion to grow. Or rather, they can’t acknowledge that their religion/theology evolves over time, because if it evolves, it wasn’t perfect from the beginning. And that challenges their understanding of their god.

Yet the real fly in the ointment is the notion of a perfect and infallible canon.

This brings me back around to what a canon is. It just means “an authoritative text,” but how that text is understood has nuances. INSPIRED ≠ INFALLIBLE. Most all followers of a canonical text believe it’s inspired by God, but not all (or even most) believe it’s infallible. (Islam is its own category here, note.) That creates some problematic GRAYS.

If it’s only inspired, written by humans with human foibles and history-locked understandings, interpreting it becomes complicated and can lead to disagreements. Taking a literalist view sweeps away the messiness. “God said it; I believe it; that settles it!” Black-and-white.

Those who believe in Biblical literalism/inerrancy (which includes a good chunk of conservative Christian Evangelicals and all Fundamentalists**) will argue the WHOLE Bible is true. If it’s written by God, it must be perfect from the get-go. Thus, a clash is created between simpler versus more nuanced views: Deuteronomy vs. Job. If an earlier view must be as true as any later one, that reduces everything to the most elementary version. It can’t evolve/grow up, yielding what feels to most like a very archaic (and often harsh) worldview.

In any case, both the traditional orthopraxic and orthodoxic religions of the ANE/Med Basin believed God/gods punished people who offended them. AND these punishments might “spill over” onto family and neighbors.

Ancient divine collateral damage.

Ironically, this is WHY early Christians were prosecuted by the pagan (e.g., traditional) Roman and Greek religious establishments. Christian failure to participate in common civic religious cult could earn divine ire. For their first two/two-and-a-half centuries, Christianity was labeled a religio illicta (illegal religion)—in part for “failure to play well with others.” E.g., make sacrifices to the appropriate Greco-Roman deities. Thus, when disaster struck, a scapegoat was sought. Those antisocial Christians are to blame! They don’t sacrifice to the gods and so, offended XXX god, who is now punishing ALL of us with YYY.

Classic ancient religious thinking, but it’s one reason I find current conservative Christian opposition to Teh Gays, trans folks, etc., enormously ironic. The persecuted have become the persecuting.

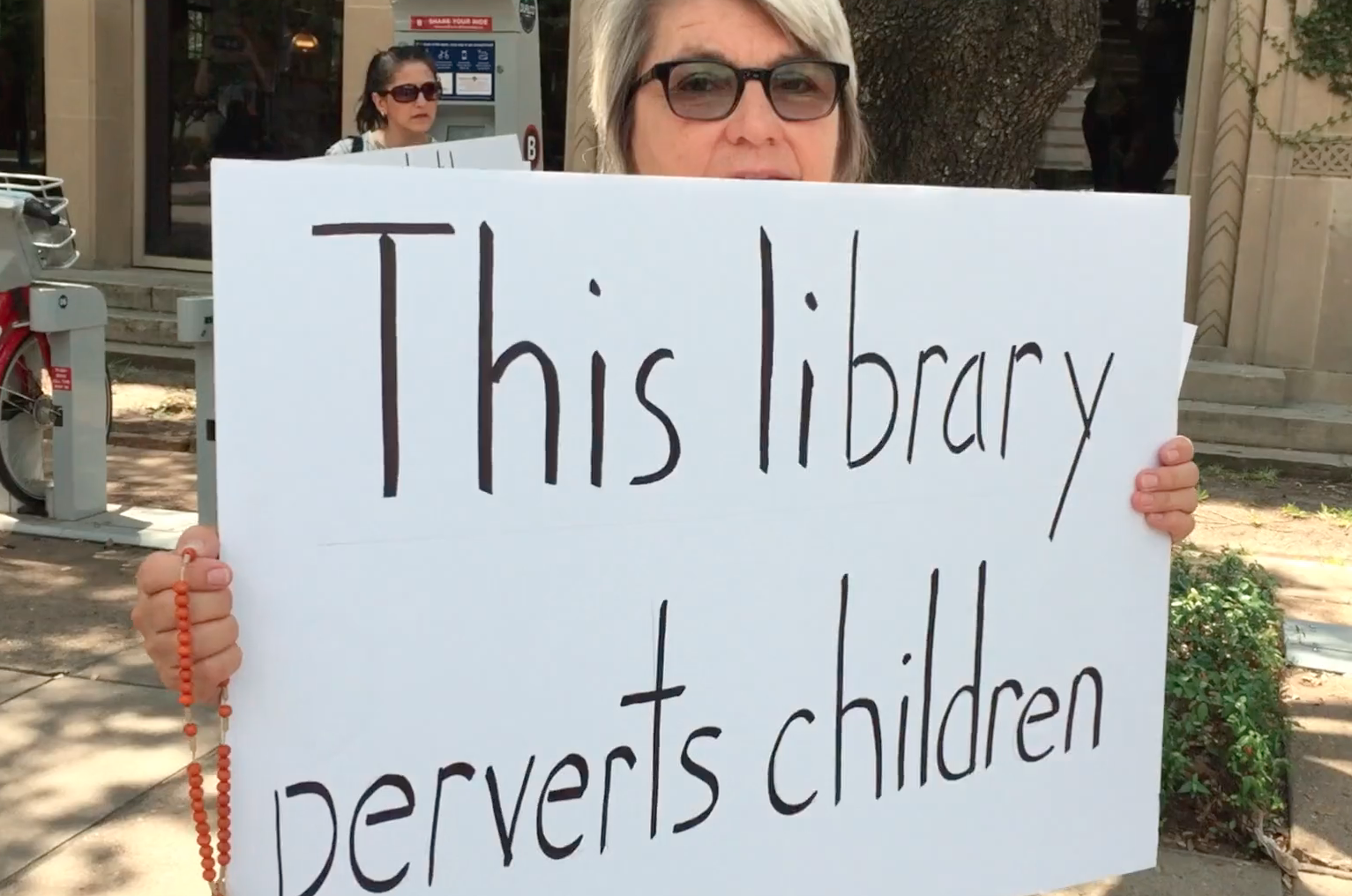

I want to emphasize that large sub-groups of Jews, Christians, and Muslims have evolved past such theologies. Yet others have not and stubbornly cling to ancient mindsets. That’s why they argue the mere presence of LGBTQI+ people will bring down the wrath of God on ALL.

Talk of “grooming” and “protecting children” is just an attempt to make palatable a belief they know won’t fly with most people, who they consider deluded by The World (e.g., the devil). Trickery is therefore required. As they’re deeply afraid themselves, they understand fear and use it to motivate others. Many are perfectly happy to make their beds with “unbelievers” long enough to get their agendas passed. God will forgive them.

This, too, is rooted in ancient ideas (discussed above) whereby a people’s own god might employ the enemy to punish them (or others). Thus, a sinful person can be utilized on the way to righteous ends because the victory of God wipes away all else. Using the enemy to effect God’s will just proves that God is in final charge of everything after all. It’s the ultimate PWN.

So if you wonder how Christian conservatives can tolerate Trump...that's why. For instance, the Hebrew Bible makes it very plain that the Persian King Cyrus (a non-Jew) is used by Yahweh to defeat Babylon and avenge the destruction of the Temple, then to release the Jews in exile there back to their homeland.

So, while some might honestly believe Trump is some sort of Jesus, many more simply don't care if he's a good person as long as he forwards what they believe to be God's Plan (e.g. ending abortion, or, more extreme: Christian Nationalism). God can use even a sinner like Trump. The ends justify the means.

I hope this helps to explain where these ideas come from, how they originally emerged, and why a subgroup of people still cling to them.

————-

* While Egypt influenced the ANE, as well as Greece and Rome, and is often shoehorned into the ANE, I consider Egypt as NE Africa. It deserves to be treated on its own, or in relation to neighbors such as Kush.

** Fundamentalists and Evangelicals tend to be equated but are not the same. Also, not all Evangelicals are conservatives (although all Fundamentalists are, by definition). Enormous variation exists between Christian denominations, which range from ultra-conservative to (surprise!) ultra-liberal. There is as much of a hard Christian Left as there is a hard Christian Right. We just tend to hear far less about them.