Quiz any of my former students, and they can probably confirm my love for maps. My most recent academic article heavily used digital mapping to demonstrate my primary argument. In virtually all my classes, I state (multiple times) that it’s hard to overemphasize the importance of geography on history, particularly in antiquity. Where people build cities, where they make roads, where they sail and trade, what sort of agriculture they could pursue…all are shaped by the land itself.

That same is true for historical

fiction, whether genre or not. A recent article in Writer’s Digest gave me Thinky-Thoughts not just about maps, but how I, personally, utilize

them in story construction. Perhaps it will be of interest for others, whether

readers or (especially) writers, even if you have no intentions of publishing.

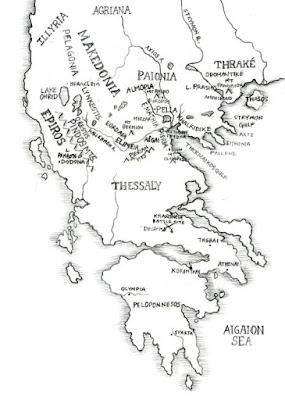

As some of you may have noticed, if you read the “fine print,” the lovely map at the front of Becoming (which I wish had also been at the front of Rise) was drawn by my very talented niece, Selena Reames, a professional artist. How cool to have two Reameses in one book? She also put up with her aunt’s rather exacting placement…”No, that’s too far west…that’s too far south.” Ha. Yet working with her helped me understand how much artistry goes into map-making. (Besides in the front of the first book, the map can be found on my website dedicated to the Dancing with the Lion series.)

Although a lot of action in both novels takes place in only three places (Pella, Mieza, and Aigai), a number of other cities and sites do show up, especially in the second book (which is why I wish the map had been put there too). Some readers don’t care, maybe a lot of readers don’t care, but it’s important to know how far away these various places are, which affects how quickly people can move between them.

Maps matter to timing events. To that end, let me share a site that I make copious use of, both for regular historicals as well as historical fantasy.

ORBIS: the StanfordGeospacial Network Model of the Roman World (Use Chrome for best results)

Yes, this is aimed at the Roman world, but can be used for other eras in the Mediterranean, and other areas not in the Mediterranean. While improvements to boats and wagons—not to mention those famous Roman roads—did affect travel speed, as well as where people could go, you can still get a ballpark estimate. Furthermore, this site allows one to choose method of transport (land, ship, riding, walking, cart, etc.), and speed (military, normal/trade, etc.). One may have to think about changes to place names, etc., but a writer can waste…er, spend a lot of time playing there.

It can ALSO be used for historicals and fantasy set in pre-modern periods, even if not in the Mediterranean, or if placed in one’s own world. Analogize. Look at miles/kilometers and terrain. Travel in mountains or forest/jungle/desert is obviously tougher than through fields, and paved roads are better than dirt, which are better than goat tracks. You also need to think about sailing seasons, and not only in cold environments. The threat of storms can make travel impossible for parts of a year.

And don’t forget it’s all general. If you’re traveling by horse with members in the party who aren’t used to day-long riding, that will slow down everybody. An inexperienced rider doesn’t just hop on a horse and go for hours. It’s not a car. I used to be a decent rider as a kid and teen, so I knew how to sit a horse, move with it, etc. But I hadn’t been riding in over two decades when I went for a 2-hour trip on Naxos, and boy, was I sore after! Experience, recent time on horseback, even age matter.

Also, ancient wagons weren’t equipped with shock absorbers, so well-maintained roads sped up travel, while poor roads slowed it down—could even halt it entirely if a wheel got stuck in a rut, came off, the axel broke…not to mention the “stuff” in the wagon (if hauling breakable objects, such as pots) had better be well-packed with straw.

With an historical such as Dancing with the Lion, the map is set. We might be able to add a few fictional places, but for the most part, we describe real space at a particular point in history.

When writing fantasy, even fantasy heavily influenced by real history, maps are unmoored and we have more freedom. Yet that can feel overwhelming to writers who don’t spend as much time as I do with maps (and climate and agriculture and battlefields, etc.).

Yet making maps—as that Writer’s Digest article describes—can help an author think about her story, even shape the plot.

My current MIP (monster-in-progress) is a projected 4-book epic fantasy series with the working title Master of Battles. When I describe it, I’m always torn on HOW to describe it. The elevator pitch is, “A fugitive shaman fleeing his wicked teacher falls over a balcony into the bedroom of a quirky prince, setting off a prophecy that will change their world.” But what I REALLY want to tell you about it the super-cool world. I not only threw up the historical pieces (events/kingdoms) but also the geographical pieces, to see where they landed.

I steal a lot from history, then hang intentionally obscure or less-known names on places and peoples, which will likely amuse Those Who Recognize but mean nothing to those who don’t. Yet I’ve mixed up the time eras, and geography too.

Creating the map was part of the fun, and that, in turn, yielded different possible outcomes.

First, if you look at our globe, you’ll notice landmasses bulk in the northern hemisphere. We’re “top heavy.” I flipped that; their world is “bottom heavy.” I also moved whole continents, in addition to changing the size of them, in order to alter outcomes. Among the biggest reasons for the massive death among indigenous populations when Europeans showed up en masse to the Americas owed to a lack of disease resistance. I think most people are aware of that; what most aren’t aware of is why.

Domesticated animals. As Coronavirus has taught us, disease can jump from animals to us. The Americas did not have horses, cattle, pigs, goats, sheep…all were imported after 1492 as part of the “Columbian Exchange.” (No really, it’s true; most folks don’t realize that.) In return, we gave Europe key crops (maize, potatoes, peppers, squash, chocolate, tobacco). But American natives just had far less resistance to small pox, etc…diseases that Europeans, Asians, and Africans had developed immunity to millennia before.

What if the Americas weren’t isolated, but had those domesticated animals earlier, and thus, disease resistance? Might make conquest harder. Also, landscape affects how warfare is conducted. As Alexander discovered in India, the phalanx doesn’t do well in a jungle, nor does cavalry. Imagine the Macedonian pike- and cavalry army trying to fight in the Amazon.

As much as I love geography and its impact on history, we must beware of geographical determinism, which is a form of proto- and not-so-proto-racism. While geography affects what we develop (sometimes for surprising reasons), as I constantly tell my students, human beings are enormously creative. If we don’t have X available, we develop Y instead, or we just figure a work-around to not having X. Therefore “civilization” should never be defined by what any given group of people has or doesn’t have, technologically speaking. The term “civilization” is problematic in the first place, but I do my best to uncouple it from specific technology (be it the wheel, iron-working, gun powder, etc.).

Take something as “basic” as writing. What is “writing” except “representative reality”? A symbol (or group of them) stands in for a word. The earliest “Old World” writing systems (Sumerian, Egyptian, Harappan, Chinese) developed symbols that were drawn/incised on a flat surface, be it clay, papyrus, stone, silk… But what if the “symbol” isn’t a mark? What if the symbol is, instead, a system of knots tied in a cord? Isn’t that also “representative reality”?

Hello, South American quipu. Or the wampum of the North American Great Lakes people. (And yes, the Chinese used knots for record-keeping, as did the Hawaiians.)We have to remember to keep our minds open.

Back to my games with maps and continents.

I moved South America across to, roughly, where Africa is—only there’s no isthmus and North America smooshed up all along the southern side (so it’s essentially one big wide continent not unlike Eurasia). Then I moved Africa to where South America is, and the northern areas are a series of larger and smaller island masses (think Australia, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines). Europe is truncated all along the north, there’s not much to Siberia at all, and the Mediterranean/Black Sea basins are longer, divided into two seas split by a sizeable archipelago. There are no Himalayas, so China was never cut off from Persia and India. In their world, the really massive empire (Shim) lies in the east, not the west (Rome). And oh, yeah, there’s a huge-ass rain forest on the southern continent full of Very Different People. And different trade.

That’s just a few of the changes I made.

Play with geography, and completely change history.

To make it more fun, on their world, not one but two sub-species of humanity survived: Aphê and Ensāni…one of whom has a functional prehensile tail. (Because who among us has never wished for a third hand?)

Hopefully, that makes readers curious about the Master of Battles series. But also, I hope it inspires other writers to think about the huge impact that geography—and therefore climate, agriculture, contact/trade, and even disease—can have on world-building, and plotting.

_composed_of_two_main_cords_with_subsidiary_and_tertiary_cords%2C_Inca%2C_Peru%2C_Late_Horizon%2C_1476-1534_AD%2C_cotton%2C_plant_fiber%2C_indigo_dye_-_Dallas_Museum_of_Art_-_DSC04703.jpg/640px-thumbnail.jpg)